E. Usha1, S Hepsibah Sharmil2*, R. Ruth Saranya3

Authors:

1MSc Nursing Candidate, College of Nursing, Dr. M.G.R Educational and Research Institute, ACS Medical College and Hospital Campus, Maduravoil, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

3Associate Professor, College of Nursing, Dr. M.G.R Educational and Research Institute, ACS Medical College and Hospital Campus, Maduravoil, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India

Corresponding Author:

2*Vice Principal & Research Scientist, College of Nursing, Dr. M.G.R Educational and Research Institute, ACS Medical College and Hospital Campus, Maduravoil, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India Mail id: hepsibah.srs@drmgrdu.ac.in

ABSTRACT

| Introduction: Practice of mothers is crucial to seek prompt medical attention especially for their under five years of aged children and it reduces the mortality rate of the children with severe acute respiratory tract infection. The aim of this study was to determine health care seeking practice of the mothers and to analyze the factors influencing mothers choice in seeking care for there under five children. Methodology: A cross sectional study was conducted at A.C.S Medical College at the three associated community health centers in Nasarathpettai, Meppur, Meppurthangal located at in Chennai. 251 mothers of under five children participated in the study. Result: The study revealed that only 61.59% of children where promptly taken to the used to GP clinic for acute respiratory tract infection and 48.34% children were treated with home remedy, 29.14% used to take to general physician. It was found that 19.21% used old prescription given for the same child and 7.95% mothers seek over the counter drugs from medical shop. Conclusion: Practice of health seeking behavior for acute respiratory infection among mothers of under five years children cannot be under estimated. It is the responsibility of the nurses and other healthcare people to create understanding on the management of acute respiratory tract infection to reduce further hazardous complication related to acute respiratory tract infection. |

Keywords: Under five children, acute respiratory infection, practice of mother, health care

| Received on 12th August 2020, Revised on 22nd August 2020, Accepted on 30th August 2020, DOI:10.36678/IJMAES.2020.V06I03.002 |

INTRODUCTION

Acute respiratory infection (ARI) causes 20 % of the mortality among under five children1. However, ARI can be preventable and the intensity of the infection can be reduced if prompt medical care is sorted. ARIs causes more death and disease prevalence in children of under five years. More studies are proving that burden of ARI is present in both urban and rural area there are affect the low class and high class children’s in equally.

In the world under five deaths due to acute respiratory infection is the fifth leading cause. Globally, about 2 to six million (16%) ARI deaths are occurring in under five children. In India 1, 58,176 under five children’s are dies in acute respiratory infection (NHFWS 2018). The medical team gives priority care for children affected with ARI especially under five children. Because most of them under five children died in ARI disease burden is high. In India the major morbidity and mortality of children under five years deaths is caused by Acute Respiratory Tract infection. In India children under five years death due to acute respiratory infection in the year of 2018 is 882,000 which is 37 per 1000 live births 2, 3.

Acute respiratory infection is divided in to two category upper respiratory infection and lower respiratory infection. The upper respiratory indicates from the nose to larynx associated with the paranasal. The lower respiratory tract is at end of the upper respiratory to alveoli (trachea, bronchi, bronchioles and alveoli). Many studies have reported that appropriate care seeking behaviors is the is the best practice. Prompt care seeking behavior is reducing the 20% of the child death rates due to acute respiratory tract infection. The mother and other to give a proper time care that should be reduce the child mortality rate.

Objectives of the Study : To assess the care seeking behaviour and practice of mothers for children with acute respiratory infection, also to associate the socio-demographic variables with mother’s care seeking behaviour on under Five children with Acute Respiratory Infection

METHODOLOGY AND METHODS

This was a community based cross– sectional study carried out in the three rural community health centers namely Nasarephpettai, Meppur and Meppurthangal which are affiliated to the tertiary level hospital at the local regions of Chennai in the state of Tamil Nadu, India. These Community health centers are located across 10 km radius away from ACS medical college. The community health centers affiliated to the tertiary level hospital are also located within 10 km between metropolitan regions of Chennai to rural land. The setting has been chosen on the basis of feasibility of adequate sample and cooperation. Population is the entire aggregation of cases which meet the designated set of criteria (Polit and Beck 2004).

The overall population of the total Nasarathaipettai population is 8409 under five children population 156. The Meppur and Meppurthangkal total population is 2182 under five children 83 the entire aggregation of cases which meet the designated set of criteria.

All the children, under five years of age belonging to the study area were included as study subjects. The mothers of the children were the respondents. Care was taken to ensure that the family of the particular under five was a permanent resident of the area and not a frequent migrant. Those who could not be contacted during the first visit were given two more visits. The research protocol was approved by the ethical committee at the ACS Medical College and Hospital and informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to inclusion in the study. A predesigned and pretested structured questionnaire was used to collect the data. The mothers were interviewed for detail information regarding socio-demographic details and acute illnesses especially ARI in last two weeks prior to the visit as these are the main contributors to child morbidity. The health care seeking behavior for such diseases including the place and person consulted for disease, the treatment availed, the money spent and the distance travelled were also enquired. Records were analyzed whenever available. Proportions and percentages were used for analysis.

Sample Size Calculation

4pq/L2 = 90 (+10 – 20%)

(Prevalence (6%), q= 1-p, L = allowable error (.05)

The Study sample comprised of 2512 under five mothers

Sampling Technique: Purposive sampling technique was used to select the sample

Selection Criteria: The Study includes mothers of less than five children; Mother’s who have already treated the acute respiratory infection for their children, Mother’s who are willing to participate and Mother’s who can speak and write Tamil and English.

Exclusion Criteria: Pilot study samples and children with other genetic problem and comorbidity.

RESULT

The analysis is a process of organizing and synthesizing the data in such a way that the research questions can be answered and the hypotheses are tested. The analysis and interpretation of the data collected from 251 mothers of under five children to assess the care seeking behaivour of mothers of less than five children with acute respiratory infection. The data was organized, tabulated and analyzed according to the objectives. Data analysis begins with description that applies to the study in which the data are numerical with some concepts. Descriptive statistics allows the researcher to organize the data and to examine the quantum of information and inferential statistics is used to determine the relationship.

Organization of the Data: Data organized under the following sections.

Section A:

Description of the demographic variables of mothers of under five children.

Section B:

Assessment of care seeking behaviour of mothers of less than five children with acute respiratory infection.

Section C:

Association of care seeking behaviour with selected demographic variables.

Section A:

Description of the demographic variables of mothers of less than five children.

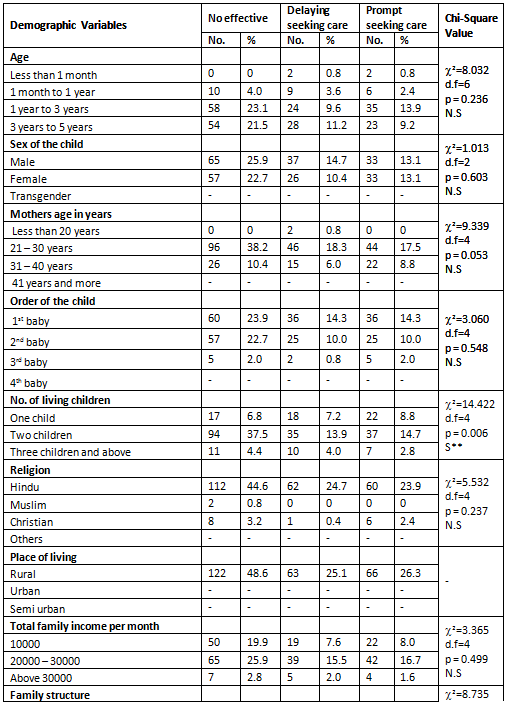

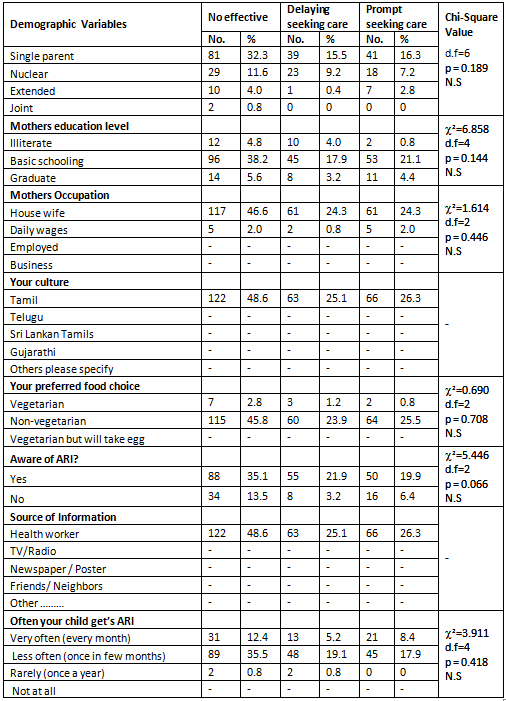

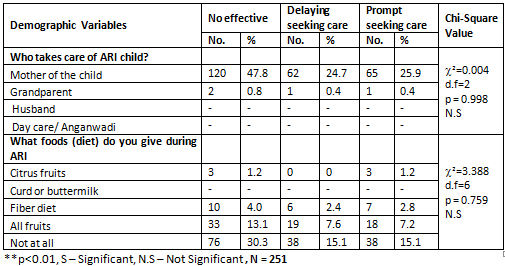

Table 1: Demographic variables of mothers of under five children (Continue…)

The table 1 shows that the demographic variable number of living children had shown statistically significant association with level of care seeking behaviour among mothers of under five children with ARI at p<0.01 level and the other demographic variables had not shown statistically significant association with level of care seeking behaviour among mothers of under five children with ARI.

The table 1 depicts that regarding age of the child, most of them 117(46.61%) were aged 1 year to 3 years, 105(41.83%) of children were aged 3 years to 5 years, 25(9.96%) were aged 1 month to 1 year and 4(1.50%) were aged less than 1 month. Considering the sex of the child, most of them 135(53.78%) were male and 116(46.22%) were female. With respect to mother’s age, most of them 186(74.10%) were in the age group of 21 – 30 years, 63(25.10%) were aged 31 – 40 years and 2(0.60%) were in the age group of less than 20 years. Regarding the order of the child, most of them 132(52.59%) were 1st baby, 107(42.63%) were 2nd born baby and 12(4.78%) were 3rd born baby. With regard to number of living children, most of them 166(66.14%) had two living children, 57(22.71%) had one child and 28(11.16%) had three and above living children. Considering the religion, most of them 234(93.23%) were Hindus, 15(5.98%) were Christians and 2(0.80%) were Muslims.

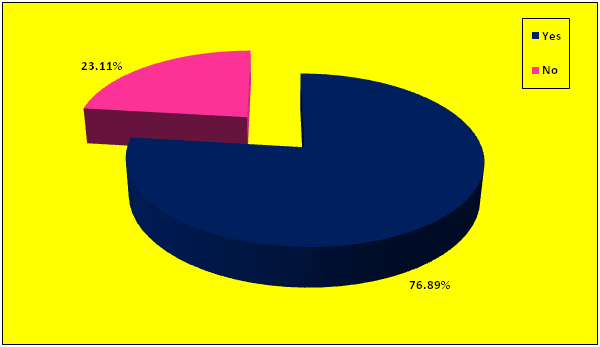

Regarding the place of living, all 251(100%) were living in rural area. The total family income per month revealed that most of them 146(58.17%) had an income of 20000 -30000, 89(35.46%) had an income of 10000 and 16(6.37%) had an income of above 30000. With respect to family structure, 161(64.14%) were single parent family, 70(27.89%) belonged to nuclear family, 18(7.17%) belonged to extended family and 2(0.80%) belonged to joint family. With regard to mother’s education level, most of them 194(77.29%) had basic schooling, 33(13.15%) were graduates and 24(9.56%) were illiterates. Regarding the mothers occupation, most of them 239(95.22%) were housewives and 12(4.78%) were daily wages. Considering the culture, all 251(100%) belonged to Tamil culture. Preferred food choice revealed that most of them 239(95.22%) were non-vegetarian and 12(4.78%) were vegetarian. Regarding the awareness of ARI, most of them 193(76.89%) had the awareness of ARI and 58(23.11%) were not aware of ARI.

Considering the source of information, all 251(100%) received information through Health Worker. With respect to how often your child get’s ARI, most of them 182(72.51%) responded as less often (once in few month), 65(25.90%) responded as very often (every month) and 4(1.59%) responded as rarely (once a year). Regarding who takes care of ARI child, most of them 247(98.41%) responded as mother and 4(1.59%) responded as grandparent. Considering the foods (diet) given to the child during ARI, most of them 152(60.56%) had not at all given food, 70(27.89%) had given all fruits, 21(9.16%) had given fiber diet and only 6(2.39%) had given citrus fruits.

Section B: Assessment of care seeking behavior of mothers of under five children with acute respiratory infection.

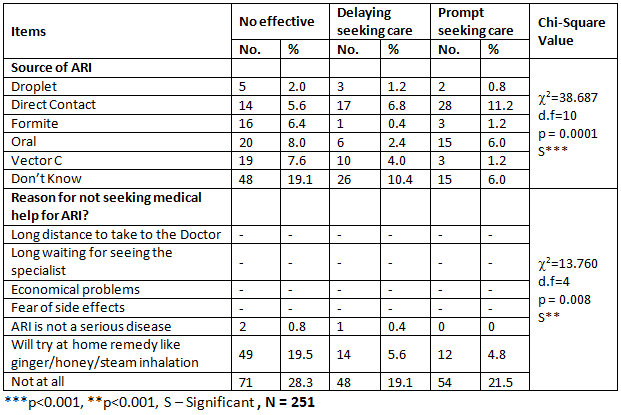

The table 2 shows that with regard to source of ARI, most of them 89(35.46%) don’t know about the source of ARI, 59(23.51%) responded as direct contact, 41(16.33%) responded as oral, 32(12.75%) responded as Vector C, 20(7.97%) responded as formite and 10(3.98%) responded as droplet. Considering the reason for not seeking medical help for ARI, most of them 173*68.92%) not at all seek medical help for ARI, 75(29.88%) used to try with home remedy like ginger/ honey/steam inhalation and only 3(1.20%) has not considered ARI is not a serious disease. Regarding the food choice you commonly give for ARI child, most of them 142(56.57%) used to give vegetarian and non-vegetarian food, 61 (24.50%) used to

give only vegetarian food, 44(17.53%) used to give milk only, 3(1.20%) used to give only non-vegetarian and only one (0.40%) used to give no mild food.

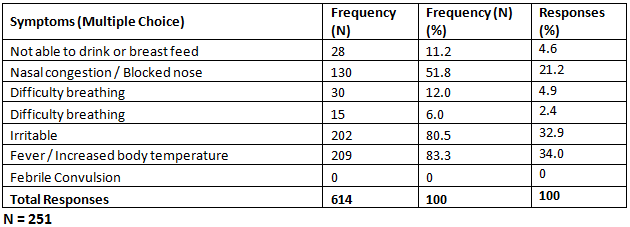

The table 3 depicts that most of them 209(80.5%) had fever / increased body temperature i.e., 34% of the total responses, 202(80.5%) had irritation which constitutes 32.9% of the total responses, 130(51.8%) has nasal congestion / blocked nose i.e., 21.2% of the total responses, 30(12%) had difficulty in breathing which constitutes 4.9% of the total responses, 28(11.2%) had not able to drink or breast feed i.e., 4.6% of the total responses and 15(6%) had difficulty in breathing i.e., 2.4% of the total responses.

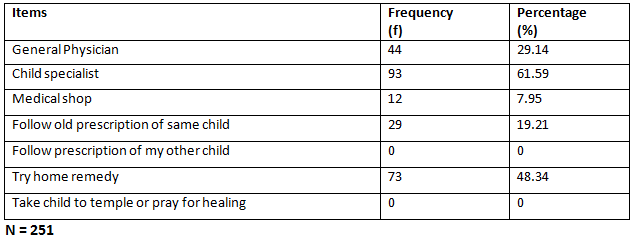

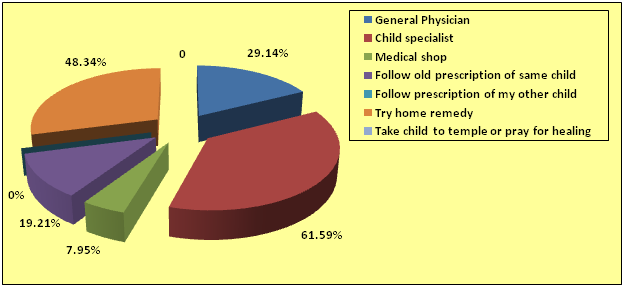

The table 5 depicts that most of them 93(61.59%) used to take to the child specialist, 73(48.34%) used to try home remedy, 44(29.14%) used to take to general physician, 29(19.21%) used to follow old prescription of same child and 12(7.95%) used to take to medical shop. The table 3 depicts that most of them 209(80.5%) had fever / increased body temperature i.e., 34% of the total responses, 202(80.5%) had irritation which constitutes 32.9% of the total responses, 130(51.8%) has nasal congestion / blocked nose i.e., 21.2% of the total responses, 30(12%) had difficulty in breathing which constitutes 4.9% of the total responses, 28(11.2%) had not able to drink or breast feed i.e., 4.6% of the total responses and 15(6%) had difficulty in breathing i.e., 2.4% of the total responses.

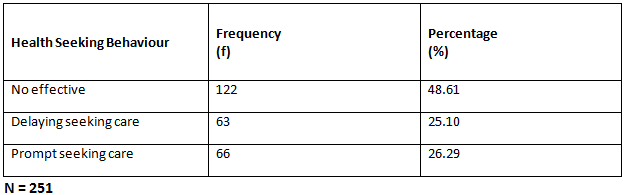

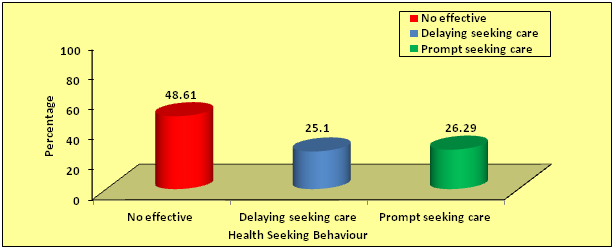

The table 5 depicts that most of them 93(61.59%) used to take to the child specialist, 73(48.34%) used to try home remedy, 44(29.14%) used to take to general physician, 29(19.21%) used to follow old prescription of same child and 12(7.95%) used to take to medical shop. The table 6 shows that most of them 122(48.61%) had no effective health seeking behaviour, 66(26.29%) had taken prompt care and 63(25.10%) had taken delayed care.

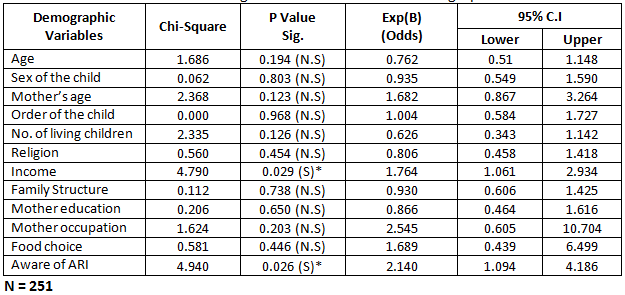

The table 7 shows the binary logistic regression analysis to find out the association of demographic variables with health seeking behaviour. The table depicts that income had shown statistically significant association with health seeking behaviour with chi-square value of (c2=4.790, p=0.029)and with an odds of 1.764. This clearly infers that income influences 1.7 times the health seeking behaviour of mothers of under five children with ARI.

The table depicts that awareness about ARI had shown statistically significant association with health seeking behaviour with chi-square value of (c2=4.940, p=0.026)and with an odds of 2.14. This clearly infers that awareness response of ‘Yes” influences 2.14 times the health seeking behaviour of mothers of under five children with ARI. The other demographic variables had not shown statistically significant association with health seeking behaviour of mothers of children with ARI.

DISCUSSION

Health seeking behavior for mothers for their child with ARI is vital. Various studies have shown that early health seeking prevents complications and equally reduces the rate of death. Studies from developing countries have reported that delay in seeking appropriate care and not seeking any care, contributes to the large number of child’s deaths4. Improving parents/caretakers health seeking behavior could contribute significantly to reducing child mortality in developing countries. The World Health Organization estimates that seeking prompt and appropriate care could reduce child’s deaths due to acute respiratory infections by 20%5. Early health seeking behavior for child’s acute health problem could reduce morbidity, short and long term complications of the child health problem, this is seen in the integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) strategy, besides improving providers skills in managing childhood illness also aims to improve parents/caretakers health care seeking behavior. The health workers are trained to teach the mothers about danger signs and counsel them about need to seek care promptly if these signs occur6 .

Epidemiologists and social scientist have devoted increasing attention to studying health-seeking behavior associated with the leading causes of child mortality, include respiratory infection. Health interview surveys conducted in different countries report varying results about the determinants of health seeking behavior during childhood illnesses (Thind & Cruz 2003). Various factors have been implicated as determinants of health seeking behavior of parents. Some studies have reported that care seeking behavior is predicted by house hold size, age and education of parents. Lack of access to health care due to high cost is perhaps the most common deterrent to optimal health care seeking in both rural and urban communities. Some studies have also shown that perceived illness severity, maternal recognition of certain signs and symptoms of childhood illness were critical factors determining health care seeking behavior7.

Mothers and Guardians as caretakers may also not seek for help or abstain from seeking care for their child health if they fail to recognize symptoms or do not consider them dangerous. In addition, once a caretaker or parents has recognized illness and decide to seek care, house hold responsibilities and long distances to health units may still delay care seeking. When health care are sought, the quality of treatment or care received might not be adequate and may cause delay in subsequent seeking for the same health care. It is to this regards to reduce respiratory infection mortality, three crucial steps in management have been suggested by UNICEF8: recognize, seek and treat. These steps are equally important. Many child deaths could be averted if timely recognition of symptoms was followed by prompt care seeking at a place where accurate diagnosis would lead to administration of right drugs in correct doses9.

In this present study the binary logistic regression analysis to find out the association of demographic variables with health seeking practice. The table depicts that income had shown statistically significant association with health seeking behaviour with chi-square value of (c2=4.790, p=0.029) and with an odds of 1.764. This clearly infers that income influences 1.7 times the health seeking behaviour of mothers of children under five years with ARI. The table depicts that awareness about ARI had shown statistically significant association with health seeking behaviour with chi-square value of (c2=4.940, p=0.026) and with an odds of 2.14. This clearly infers that awareness response of ‘Yes” influences 2.14 times the health seeking behaviour of mothers of under five children with ARI. The other demographic variables had not shown statistically significant association with health seeking behaviour of mothers of children with ARI. Infants (0–11 months) are more commonly cared by care takers rather than the parents and boys more than girls. Mothers below 35 years of age, who completed secondary education and those who marry at a young age, present with the good in terms of caring for their sick children. Mothers who received professional antenatal care have an advantage of bearing healthy children less prone to infections. Previous Studies found that maternal age has effect on care given to children in families in term of health. For rural residents, younger mothers aged between 15–34 years are said to be more active in seeking health care than for older mothers over 35 years of age. In urban residents, mothers less than 25 years old present with more health seeking behavior than those over 25 years of age. It is also reported that younger families are more exposed to media communications than older families due to a higher education level, which might contribute to broad information received on health issues leading to better health seeking behaviors by those young mothers. According to Mukandoli 10, young mothers and males were found to be associated with prolonged delay in seeking health care. Previous study also revealed that the health seeking behavior of a community determines how health services are used and in turn the health outcomes of populations.

Factors that determine health behavior may be physical, socio-economic, cultural or political. Indeed, the utilization of a health care system may depend on educational levels, economic factors, cultural beliefs and practices. Other factors include environmental conditions, socio-demographic factors, knowledge about the facilities, gender issues, political environment, and the health care system itself11. However, it is observed that socioeconomic, socio-cultural and demographic factors are often ignored while formulating health policies or any schemes for providing health care facilities to people. As a result, new schemes for providing health care services could not achieve its goal. Thus, health seeking behaviour is directed by socioeconomic, socio-cultural, and demographic factors, influence the health behaviour. In addition, according to Okwaraji et al12 in effect of geographical access to health facilities on child mortality in rural Rwanda: a community based cross sectional study, small sized families thought more about their children’s medical attention for respiratory infection in rural and urban residence as opposed to large families. Families with more than 4 children suffer more not only economically but also in regards to concentrated and time spent with their sick child. This reason was more pronounced with urban residences perhaps due to difference in average family members. In urban households average 3.7 persons compared to rural households with 4.9 persons.

Ethical clearance: The institution review committee of ACS Medical College and Hospital, DR MGR Educational and Research Institute, Chennai, has granted ethical clearance for the study with reference number 19/2019/IEC/ACSMCH dated 09/10/2019.

Conflict of interest: There was no conflict of interest to conduct this study.

Fund for the study: It was self-financed study.

CONCLUSION

The study concluded that most of them 93(61.59%) used to take to the child specialist, 73(48.34%) used to try home remedy, 44(29.14%) used to take to general physician, 29(19.21%) used to follow old prescription of same child and 12(7.95%) used to take to medical shop.

The results can help the health seeking behavior on acute respiratory infection among under five mothers understand various aspects of self-management and other health care personal managements of under-five mothers and follow up13, 14. It is the responsibility of the nurses15 to create understanding on the management of acute respiratory tract infection of to reduce further complication related to acute respiratory tract infection.

REFERENCES

1. Dagne, H., et al., (2020). Acute respiratory infection and its associated factors among children under-five years attending pediatrics ward at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: institution-based cross-sectional study. BMC pediatrics,20(1): p.1-7.

2. Krishnan, A., et al., (2015). Epidemiology of acute respiratory infections in children-preliminary results of a cohort in a rural north Indian community. BMC infectious diseases, 15(1): p. 1-10.

3. Imran, M., et al., (2019). Risk factors for acute respiratory infection in children younger than five years in Bangladesh. Public health, 173: p. 112-119.

4. Sreeramareddy, C.T., et al., (2006). Care seeking behavior for childhood illness-a questionnaire survey in western Nepal. BMC international health and human rights, 6(1): p. 7.

5. Källander, K., et al., (2008). Delayed care seeking for fatal pneumonia in children aged under five years in Uganda: a case-series study. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 86: p. 332-338.

6. Stewart, M.K., et al., (1993).Acute respiratory infections (ARI) in rural Bangladesh: perceptions and practices. Medical anthropology,. 15(4): p. 377-394.

7. Ferdous, F., et al., (2014). Mothers’ perception and healthcare seeking behavior of pneumonia children in rural Bangladesh. ISRN family medicine.

8. Mathew, J.L., et al., (2011). Acute respiratory infection and pneumonia in India: a systematic review of literature for advocacy and action: UNICEF-PHFI series on newborn and child health, India. Indian pediatrics, 48(3): p. 191.

9. Williams, B.G., et al., (2002). Estimates of world-wide distribution of child deaths from acute respiratory infections. The Lancet infectious diseases, 2(1): p. 25-32.

10. Mukandoli, E., (2017). Health seeking behaviors of parents/caretakers of children with severe respiratory infections in a selected referral hospital in Rwanda. University of Rwanda.

11. Francis Jebaraj, H.S., (2015).Stopping the run-around: addressing Aboriginal community people’s mental health and alcohol and drug comorbidity service needs in the Salisbury and Playford local government areas of South Australia.

12. Okwaraji, Y.B., et al., (2012). Effect of geographical access to health facilities on child mortality in rural Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. Plos one, 7(3): p. e33564.

13. Hepsibah S Francis, Unit 4; (2020). Guidance and Counciling in Essentials of Commun-ication and Educational Technology for BSc Nursing, K.C. Gopichandran. L, Editor. CBS Publishers and Distributors Pvt. Ltd. : Delhi.

14. Sharmil, H., (2019).Health Information Technology Media by Nurses in Patient Care. International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation, 2(2): p. 290235.

15. Sharmil,S.H.,(2011). Awareness of Commu- nity Health Nurses on Legal Aspects of Health Care. International Journal of Public Health Research,(Special issue): p. 199-212.

| Citation: E. Usha, S Hepsibah Sharmil, R. Ruth Saranya (2020). Practice of mothers to seek medical attention for their children with acute respiratory infection, ijmaes; 6 (3); 770-783. |

Leave a Reply